Today I'm excited to let you know about a great new workshop offering from the Potters Council and Ceramic Arts Daily: One-day workshops with master artists. If you're looking for an in-depth, intimate, inspirational workshop experience, these new workshops are for you.

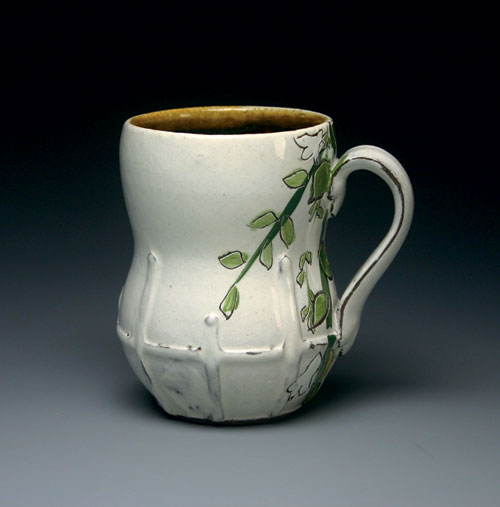

Held at our video studio here in Columbus, Ohio, the first of these workshops, Design for the Soft Surface, takes place January 19, 2013, and features artist Ben Carter. In today's post, I thought I would share a virtual visit to Ben's Shanghai ceramics studio so you can get to know him a little better! - Jennifer Poellot Harnetty, editor

Studio

I

moved to China in early 2010 to accept the position of educational director at the Pottery Workshop Shanghai. While this 7000 mile move took me away from friends and family, I was excited to experience a culture whose pottery tradition is thousands

of years old. From terra cotta roof tiles to porcelain Meiping vases, China's cultural foundation is built on clay.

The opportunity to manage a studio overseas has been exciting, challenging, and rewarding. Overcoming the language barrier has been a great source of humor for myself and my colleagues. For example, when my name is pronounced by native Mandarin speakers,

it is remarkably similar to the word for stupid. This word play has been an easy way to diffuse the tension that cultural differences can create. Through teaching in a multinational studio, I have come to understand that the love of clay is a great

unifier. I often see students who do not share a common language laughing with each other as they use hand gestures to explain their ideas.

<Not

long after my arrival, we moved our studio to a newly remodeled location. Our team of experienced potters designed the perfect studio. Floor drains, movable kiln vent hoods, copious wall sockets, a specialized glaze lab, and an in-house coffee shop

are just a few of the features that make our studio exceptional.

The most unique aspect of our studio is the character of its location. We are tucked down a quiet nong tang (or alley) in the heart of the French concession, a major area for international commerce since the late 1800s. In a frenetic city of over 20 million

residents, we have established a creative oasis for ceramic artists. The only downside to our urban setting is the lack of storage space. Our solution has been off-site storage in a 1940s bomb shelter that also doubles as a shipping depot for banana

distribution. We hand carry raw materials down a flight of steps between the studio and the storage room. While this is good exercise, it is quite a task considering our in-house trading company supplies tons of raw materials to schools around the

country. Our spatial limitations force efficient studio management. As a result we have the cleanest and most well organized studio that I have seen in China.

Being

in a community studio has altered the way I work. For the previous seven years I shared semi-private studio space with no more than a handful of people. I currently share my 1000-square-foot studio with 35 students, 6 renters, and up to 100 group-class

participants every month. In my old studios, I was able to lay out slab-built forms on large tables. As they dried, I worked on thrown forms. This rhythm of making was very productive for me. I would make pots for a week and then spend a week decorating.

In our tightly packed studio, this work pattern is not possible. My work must fit on one roller cart at the end of each day. It now takes twice as long to make the same amount of work. This change of pace has been a blessing in disguise, because I

spend more time handling, and therefore thinking about, each individual piece. As a former production potter, my instinct for bigger, faster, lighter often leads me to sacrifice creativity for output. My change of studio has shifted my motivation

from quantity to quality.

Materials

Relocating

to a new continent challenged me to work with new materials. As an earthenware potter, the lack of standardized frits made low-fire pottery a difficult option. The switch from cone 03 to cone 6 provided a new area of ceramic chemistry to explore.

In the past I relied on a glaze-calculation program to aid with testing, but Chinese suppliers provide no chemical analysis for their materials. Materials can change radically from one batch to the next so every bag must be tested. My research progressed

slowly through trial and error. My dedicated coworkers and I used hundreds of test tiles to develop eight stable glazes.

Finding a versatile clay body presents another interesting challenge. In the United States, clays are blended for maximum plasticity and strength. In contrast, clay making in China follows the “what you see is what you getâ€

mentality. Traditionally artisans adapted production processes to the unique characteristics of their clay, developing regional styles that owed much of their aesthetic to the material. Altering the clay to meet my own needs has been surprisingly

complicated. For example, in a quest for better throwing clay I added the plasticizer bentonite. Chinese bentonite is not finely milled thus making its properties similar to fine grog, so it actually decreased plasticity in the clay body. This counter-intuitive

outcome forced me to adapt my style to the material. My throwing skills have increased from the need to out maneuver less plastic clay bodies. Using unfamiliar materials has helped me become more flexible in my studio practice. My first year was spent

testing clays, slips, and glazes to find a combination that fit my aesthetic. In the end, I settled on stoneware from Yixing, porcelain slip from Jingdezhen, and commercial underglazes and glazes from the Chrysanthos Company. With a solid group of

materials, I am again producing a larger amount of work for exhibitions.

Paying Dues (and Bills)

My

ceramic training started in a high school that offered many art courses. My teachers encouraged my interest and gave me a strong foundation in ceramics. In 1998, I enrolled at Appalachian State University to study art education. The proximity of the

school to the Penland area helped me tap into the vibrant arts community in western North Carolina. This wellspring of knowledge taught me the ins and outs of daily studio life. After graduating, my studio assistant jobs were a great introduction

to running a small business. In 2007, I sought an MFA in ceramics from the University of Florida in Gainesville. The academic setting pushed me conceptually and filled the gaps in my technical knowledge. All of these experiences have been essential

in developing my understanding of clay and business.

Although I officially started my ceramic business in 2004, I have supplemented my income with production work or teaching. The majority of my time is now focused on managing the Pottery Workshop Shanghai. I spend around 50 hours a week in the studio.

Half of my time is spent on marketing and other administrative duties. The other half is split between teaching and making my own work.

Most Valuable Lesson

I am conscious not to segregate myself into a fixed idea about what art should be. Challenging my understanding welcomes change in my perspective and beliefs. Moving abroad has greatly helped me get out of my ideological comfort zone and into an active

state of learning. One aspect of being open-minded is accepting the advice of more experienced members in our field. My mentors have been gracious in sharing their hardship and success. Learning from their experience has enabled me to explore new

directions. Open communication within our community is one of the most attractive features of our profession.

Get a taste of Ben's techniques in this post from the Ceramic Arts Daily archives!

Search the Daily

Published Oct 29, 2012

Held at our video studio here in Columbus, Ohio, the first of these workshops, Design for the Soft Surface, takes place January 19, 2013, and features artist Ben Carter. In today's post, I thought I would share a virtual visit to Ben's Shanghai ceramics studio so you can get to know him a little better! - Jennifer Poellot Harnetty, editor

Studio

The opportunity to manage a studio overseas has been exciting, challenging, and rewarding. Overcoming the language barrier has been a great source of humor for myself and my colleagues. For example, when my name is pronounced by native Mandarin speakers, it is remarkably similar to the word for stupid. This word play has been an easy way to diffuse the tension that cultural differences can create. Through teaching in a multinational studio, I have come to understand that the love of clay is a great unifier. I often see students who do not share a common language laughing with each other as they use hand gestures to explain their ideas.

< Not

long after my arrival, we moved our studio to a newly remodeled location. Our team of experienced potters designed the perfect studio. Floor drains, movable kiln vent hoods, copious wall sockets, a specialized glaze lab, and an in-house coffee shop

are just a few of the features that make our studio exceptional.

Not

long after my arrival, we moved our studio to a newly remodeled location. Our team of experienced potters designed the perfect studio. Floor drains, movable kiln vent hoods, copious wall sockets, a specialized glaze lab, and an in-house coffee shop

are just a few of the features that make our studio exceptional.

The most unique aspect of our studio is the character of its location. We are tucked down a quiet nong tang (or alley) in the heart of the French concession, a major area for international commerce since the late 1800s. In a frenetic city of over 20 million residents, we have established a creative oasis for ceramic artists. The only downside to our urban setting is the lack of storage space. Our solution has been off-site storage in a 1940s bomb shelter that also doubles as a shipping depot for banana distribution. We hand carry raw materials down a flight of steps between the studio and the storage room. While this is good exercise, it is quite a task considering our in-house trading company supplies tons of raw materials to schools around the country. Our spatial limitations force efficient studio management. As a result we have the cleanest and most well organized studio that I have seen in China.

Materials

Finding a versatile clay body presents another interesting challenge. In the United States, clays are blended for maximum plasticity and strength. In contrast, clay making in China follows the “what you see is what you get†mentality. Traditionally artisans adapted production processes to the unique characteristics of their clay, developing regional styles that owed much of their aesthetic to the material. Altering the clay to meet my own needs has been surprisingly complicated. For example, in a quest for better throwing clay I added the plasticizer bentonite. Chinese bentonite is not finely milled thus making its properties similar to fine grog, so it actually decreased plasticity in the clay body. This counter-intuitive outcome forced me to adapt my style to the material. My throwing skills have increased from the need to out maneuver less plastic clay bodies. Using unfamiliar materials has helped me become more flexible in my studio practice. My first year was spent testing clays, slips, and glazes to find a combination that fit my aesthetic. In the end, I settled on stoneware from Yixing, porcelain slip from Jingdezhen, and commercial underglazes and glazes from the Chrysanthos Company. With a solid group of materials, I am again producing a larger amount of work for exhibitions.

Paying Dues (and Bills)

Although I officially started my ceramic business in 2004, I have supplemented my income with production work or teaching. The majority of my time is now focused on managing the Pottery Workshop Shanghai. I spend around 50 hours a week in the studio. Half of my time is spent on marketing and other administrative duties. The other half is split between teaching and making my own work.

Most Valuable Lesson

I am conscious not to segregate myself into a fixed idea about what art should be. Challenging my understanding welcomes change in my perspective and beliefs. Moving abroad has greatly helped me get out of my ideological comfort zone and into an active state of learning. One aspect of being open-minded is accepting the advice of more experienced members in our field. My mentors have been gracious in sharing their hardship and success. Learning from their experience has enabled me to explore new directions. Open communication within our community is one of the most attractive features of our profession.

Get a taste of Ben's techniques in this post from the Ceramic Arts Daily archives!

Unfamiliar with any terms in this article? Browse our glossary of pottery terms!

Related Content

Ceramic Artists

Functional Pottery

Ceramic Sculpture

Glaze Chemistry

High-Fire Glaze Recipes

Mid-Range Glaze Recipes

Low-Fire Glaze Recipes

Ceramic Colorants

Ceramic Glazes and Underglazes

Ceramic Raw Materials

Pottery Clay

Ceramic Decorating Tools

Ceramic Kilns

Making Clay Tools

Wheel Throwing Tools

Electric Kiln Firing

Gas Kiln Firing

Raku Firing

Salt Firing and Soda Firing

Wood Kiln Firing

Ceramic Decorating Techniques

Ceramic Glazing Techniques

Handbuilding Techniques

Making Ceramic Molds

Making Ceramic Tile

Wheel Throwing Techniques