Chromium oxide is a relatively finicky glaze additive, specifically in the presence of tin oxide at opacifying amounts. Even an increase in weight of 0.01 grams can change your glaze from a delicate light pink to a striking deep red. But why is this?

Defining the Terms

Crystal Lattice: The symmetrical and 3-D arrangement of atoms in a crystalline solid (think diamonds and salt). Empty spaces within the lattice can be occupied by other molecules, ions, and atoms. This could change the structure, color, and properties of the lattice.

Nanoparticles: Just a super tiny particle (1–100 nanometers in size). It can even have different properties than bigger particles of the same material.

Opacity: A glaze’s opacity dictates how much light passes through the glaze profile, interacts with the clay surface, and reflects back out. A glaze with a high opacity allows little to no light to pass through, while low opacity allows more light, resulting in a translucent glaze.

Plasmon Resonance: This color mechanism occurs when a photon of light hits a nanoparticle surface and excites electrons on the surface, causing them to oscillate around the particle. The size of the particle dictates the absorption wavelength of light and thus visible color.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): A type of microscopy technique in which electrons are projected through a thin sample, producing a high-resolution and super-high-magnification image.

Chromium Oxide in Glazes

Chromium oxide (Cr2O3) is a green pigment that is used in a variety of glazes and is best known for producing a medium green. Typically, it is a low-metal-loading/ weight-efficient green pigment that is also used for complex blacks and charcoal blends in combination with iron and cobalt. In addition, 0.15–0.2% chromium oxide is widely used in combination with 5–7.5% tin oxide to produce a range of known raspberry red glazes for mid-range oxidation firings. Possibly the most effective of strong pigments, chromium is only necessary in relatively small amounts to produce striking colors. While most other metal oxide and carbonate pigments rely on d-orbital splitting for their color mechanism (as chromium does without the presence of tin), chromium raspberries seem to work differently—and no one wants to talk about why.

With a better understanding of the mechanism for producing raspberry reds, vibrant pinks, and purples, these hues can easily be achieved for a fraction of the price of rare earths or costly stains that have a limited color palette (1).

For example, with only chromium as a pigment at 0.2% loading, a medium green is produced. Upon introducing tin oxide in 1% increments, the tile color shifts from a green to a deep raspberry red at 6% (2). This is, mechanistically, ridiculous. Tin is a notorious whitener. It is in high-end toothpastes to “stain” your teeth white. It is in white paint. If you add white to green, it does not make red. Something else entirely is actually taking place.

Transmission electron microscopy allows for imaging of nanoparticles suspended in the glaze. This happens early on, but a color change is observable in the presence of cassiterite (tin oxide grains forming in the glaze) and nanoparticles form. It is hard to tell exactly what they are (just chromium oxide, or chromium-tin alloy?) without EDS spectra from the TEM, but literature suggests that they are Cr2O3 nanoparticles organized around cassiterite grains in the glaze material.

From the trend in the green-to-red tiles (2), when tin is added to a 0.20% chromium base (at around 5% SnO2), a deep red color forms. The mechanism of this transition is still highly debated, but some interaction between chromium oxide and tin oxide creates this unexpected range of colors. TEM imaging (and literature sources) suggest that some amount of chromium oxide nanoparticles form around the presence of cassiterite—effectively the mineral form of tin oxide.1 This is also potentially why tin is an opacifier. At right around 4–5%, there is enough tin oxide in the glaze for cassiterite grains to form, shortening the path length of light into the glaze, reflecting light, and leading to opacity. While nanoparticle reds are most often due to plasmon resonance2—absorption of light and oscillation of electrons around a particle surface, which creates the notorious nanoparticle red—other literature sources suggest that chromium is incorporated into the cassiterite structure.3,4 From this, a higher chromium and lower zinc content results in green because there is an excess of chromium that cannot be incorporated into the structure.

Pink!

If you’ve done any degree of searching for recipes, there are significant limitations to pink glazes and even pigments/stains. A quick search online or in any pottery supply store shows a diverse array of all the glazes in shades of greens and blues that one could hope for, but few pinks. But, apart from Mason stains (and even then, the shades are limited), the variety and availability of pink glazes are disappointing at best.

The most reliable standard for pink glazes, erbium oxide (Er2O3), is a rare earth metal that produces a translucent light pink in 8–10% amounts (3). While erbium produces this highly sought-after light pink, it is relatively unaffordable for most to casually mix up a bucket. One pound of erbium oxide goes for about $120, while a pound of chromium oxide is about $28 (and you use 2000-fold less by weight!). In addition, chromium oxide produces a light pink, similar to that of erbium oxide, at around 0.005%, much less than the already more expensive erbium. The addition of 10% erbium oxide in 10,000 grams of glaze (about 2⁄3 of a standard 5-gallon bucket) would be around $264. In comparison, the addition of 0.005% chromium oxide and 5% tin oxide to 10,000 grams of glaze would cost around $141 (the large majority of this due to the addition of tin oxide, as the chromium oxide alone would only cost three cents).

Other pink glazes tend to be difficult to use and are limited to specific conditions, such as coating thickness and firing temperatures.

In attempts to create a new pink standard, one that is highly more affordable and easier to use, we started with the raspberry chromium oxide glaze. This glaze has a high cassiterite concentration (tin oxide (SnO2)). Cassiterite forms a crystal structure which helps prevent light from traveling through the glaze—creating an opacifying effect. In order to produce pink (rather than a deep red), we started scaling back the amount of chromium oxide introduced to the 5% SnO2 glaze from figure 2, as that was when a clear, unmuddied red was first observed. If there is a lower concentration of chromium oxide to occupy the tin crystal lattice, and the same overall opacity, a lower saturation and more pastel red should be found. After eighteen chromium down-ramps, we found that while most red chromium glazes use around 0.2% chromium oxide, even 0.005% chromium oxide was enough to produce a soft pink, while anything at or above 0.025% seems to transition back toward the deeper raspberry red colors (4).

While these chromium amounts yield the desired shades of pink, they also produce speckles—possibly due to concentrated color centers. These color centers likely arise from defects in the structure of the tin-chromium lattice. While the speckling may be an effect that is desirable to some, it can be reduced by using a ball mill to evenly distribute the chromium oxide.5

With pinks set, it was pondered if purples could also be developed the same way. Traditionally, purples (similarly to pinks) are hard. The most common purple is neodymium oxide, making a dichroic lavender. It has about the same cost as erbium: $120/pound. And the pigment loading for neodymium is about the same, ringing in at 8% or so. That’s more than $200 for a bucket in just pigment alone.

Cobalt is a relatively strong pigment (but not so sensitive as chromium in tin, as shown earlier), so it was added in 0.05% increments and then doubled in the last row at 0.40%. This made for quite a colorful set of glazes that, to our knowledge, hasn’t been developed or shared to this date (5).

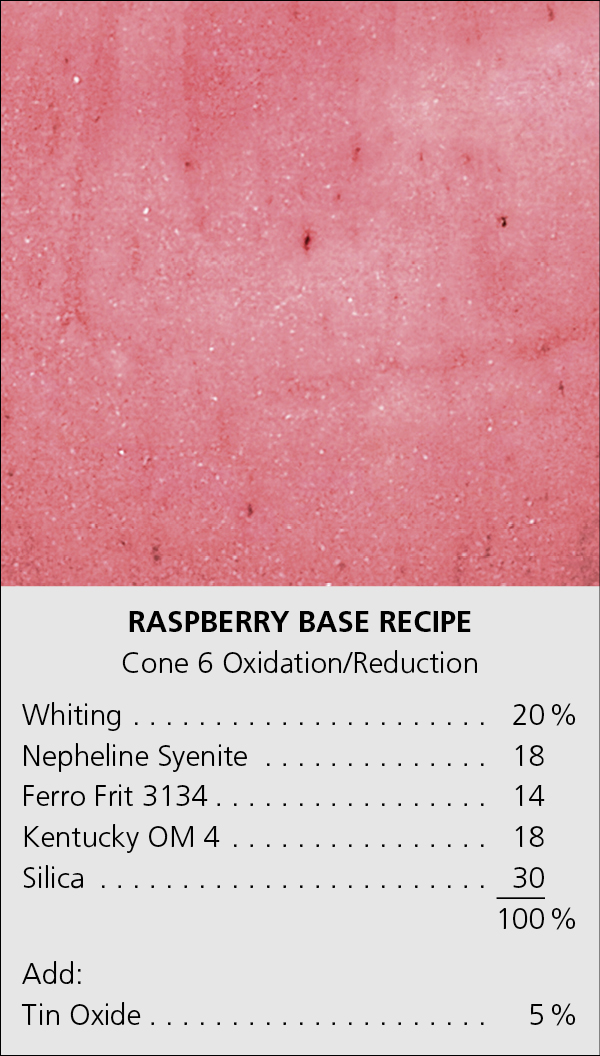

Raspberry Base Recipe

This is the base recipe for tin and chrome glazes to produce pinks and purples. Ferro frit 3134 provides a high calcium content that is essential in achieving the desired pink color.6 Calcium (in Ferro frit 3134) helps achieve opacity in the glaze at higher temperatures.7 It should also be noted that zinc should be avoided in this glaze recipe as it results in varying shades of brown. This could be because zinc could compete with chromium for open sites in the cassiterite crystal matrix (which chromium otherwise occupies and results in vibrant pinks and raspberries).

To obtain Julia’s Pink, as seen in the first mug for this article, add 0.010% Cr2O3 to the Raspberry Base Recipe. Be sure to pay attention to decimal places. It will be a very small amount of chromium!

While the exact mechanism for chromium-tin pink and raspberry glazes is not currently fully agreed upon, several different phenomena are taking place, including nanoparticle formation, chromium substitution in cassiterite matrix, and likely competition between Cr and Sn for that matrix position. It is interesting that nanomaterial quantities of chromium oxide are required for vibrant pinks and reds—much akin to metal loading content for nanoparticle gold and silver glazes as well.

Hopefully, this grid of pinks to purples helps those in need and inspires others to look at commonly used recipes and ask themselves how they work—and then start changing additives in the recipes. This range of pinks and purples has been sitting under potters’ noses for a decade now, just waiting for someone to ask how it works.

the authors Julia Krichev is a swimmer at the University of Richmond. She is currently studying biochemistry and visual arts at the University of Richmond.

Craig Caudill is currently pursuing a master’s of public health in epidemiology at the University of Michigan. He is a recent graduate from the University of Richmond, earning a BA with honors in leadership studies.

Ryan Coppage is currently chemistry teaching faculty at the University of Richmond. He fiddles with various glaze projects and makes a reasonable number of pots. To see more, visit www.ryancoppage.com.

1 Castro, R. H. R. et al. Surface Segregation in Chromium-Doped Nanocrystalline Tin Dioxide Pigments. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 95, 170–176 (2012). 2 Amendola, V., Pilot, R., Frasconi, M., Maragò, O. M. & Iatì, M. A. Surface plasmon resonance in gold nanoparticles: a review. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 203002 (2017). 3 Julián, B. et al. A Study of the Method of Synthesis and Chromatic Properties of the Cr-SnO2 Pigment. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 2694–2700 (2002). 4 Tena, M. A. et al. Study of Cr-SnO2 ceramic pigment and of Ti/Sn ratio on formation and coloration of these materials. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 27, 215–221 (2007). 5 Technofile: Demystifying Chrome Oxide for Fantastic Ceramic Glaze Color. https://ceramicartsnetwork.org/daily/article/Technofile-Demystifying-Chrome-Oxide-for-Fantastic-Ceramic-Glaze-Color. 6 Ibid. 7 Opacifiers. https://ceramicartsnetwork.org/ceramic-recipes/recipe/Opacifiers.

We understand your email address is private. You will receive emails and newsletters from Ceramic Arts Network. We will never share your information except as outlined in our privacy policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Please enjoy this complimentary article for the month.

For unlimited access to Ceramics Monthly premium content, please subscribe.

We understand your email address is private. You will receive emails and newsletters from Ceramic Arts Network. We will never share your information except as outlined in our privacy policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Subscribe to Ceramics Monthly

Chromium oxide is a relatively finicky glaze additive, specifically in the presence of tin oxide at opacifying amounts. Even an increase in weight of 0.01 grams can change your glaze from a delicate light pink to a striking deep red. But why is this?

Defining the Terms

Crystal Lattice: The symmetrical and 3-D arrangement of atoms in a crystalline solid (think diamonds and salt). Empty spaces within the lattice can be occupied by other molecules, ions, and atoms. This could change the structure, color, and properties of the lattice.

Nanoparticles: Just a super tiny particle (1–100 nanometers in size). It can even have different properties than bigger particles of the same material.

Opacity: A glaze’s opacity dictates how much light passes through the glaze profile, interacts with the clay surface, and reflects back out. A glaze with a high opacity allows little to no light to pass through, while low opacity allows more light, resulting in a translucent glaze.

Plasmon Resonance: This color mechanism occurs when a photon of light hits a nanoparticle surface and excites electrons on the surface, causing them to oscillate around the particle. The size of the particle dictates the absorption wavelength of light and thus visible color.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): A type of microscopy technique in which electrons are projected through a thin sample, producing a high-resolution and super-high-magnification image.

Chromium Oxide in Glazes

Chromium oxide (Cr2O3) is a green pigment that is used in a variety of glazes and is best known for producing a medium green. Typically, it is a low-metal-loading/ weight-efficient green pigment that is also used for complex blacks and charcoal blends in combination with iron and cobalt. In addition, 0.15–0.2% chromium oxide is widely used in combination with 5–7.5% tin oxide to produce a range of known raspberry red glazes for mid-range oxidation firings. Possibly the most effective of strong pigments, chromium is only necessary in relatively small amounts to produce striking colors. While most other metal oxide and carbonate pigments rely on d-orbital splitting for their color mechanism (as chromium does without the presence of tin), chromium raspberries seem to work differently—and no one wants to talk about why.

With a better understanding of the mechanism for producing raspberry reds, vibrant pinks, and purples, these hues can easily be achieved for a fraction of the price of rare earths or costly stains that have a limited color palette (1).

For example, with only chromium as a pigment at 0.2% loading, a medium green is produced. Upon introducing tin oxide in 1% increments, the tile color shifts from a green to a deep raspberry red at 6% (2). This is, mechanistically, ridiculous. Tin is a notorious whitener. It is in high-end toothpastes to “stain” your teeth white. It is in white paint. If you add white to green, it does not make red. Something else entirely is actually taking place.

Transmission electron microscopy allows for imaging of nanoparticles suspended in the glaze. This happens early on, but a color change is observable in the presence of cassiterite (tin oxide grains forming in the glaze) and nanoparticles form. It is hard to tell exactly what they are (just chromium oxide, or chromium-tin alloy?) without EDS spectra from the TEM, but literature suggests that they are Cr2O3 nanoparticles organized around cassiterite grains in the glaze material.

From the trend in the green-to-red tiles (2), when tin is added to a 0.20% chromium base (at around 5% SnO2), a deep red color forms. The mechanism of this transition is still highly debated, but some interaction between chromium oxide and tin oxide creates this unexpected range of colors. TEM imaging (and literature sources) suggest that some amount of chromium oxide nanoparticles form around the presence of cassiterite—effectively the mineral form of tin oxide.1 This is also potentially why tin is an opacifier. At right around 4–5%, there is enough tin oxide in the glaze for cassiterite grains to form, shortening the path length of light into the glaze, reflecting light, and leading to opacity. While nanoparticle reds are most often due to plasmon resonance2—absorption of light and oscillation of electrons around a particle surface, which creates the notorious nanoparticle red—other literature sources suggest that chromium is incorporated into the cassiterite structure.3,4 From this, a higher chromium and lower zinc content results in green because there is an excess of chromium that cannot be incorporated into the structure.

Pink!

If you’ve done any degree of searching for recipes, there are significant limitations to pink glazes and even pigments/stains. A quick search online or in any pottery supply store shows a diverse array of all the glazes in shades of greens and blues that one could hope for, but few pinks. But, apart from Mason stains (and even then, the shades are limited), the variety and availability of pink glazes are disappointing at best.

The most reliable standard for pink glazes, erbium oxide (Er2O3), is a rare earth metal that produces a translucent light pink in 8–10% amounts (3). While erbium produces this highly sought-after light pink, it is relatively unaffordable for most to casually mix up a bucket. One pound of erbium oxide goes for about $120, while a pound of chromium oxide is about $28 (and you use 2000-fold less by weight!). In addition, chromium oxide produces a light pink, similar to that of erbium oxide, at around 0.005%, much less than the already more expensive erbium. The addition of 10% erbium oxide in 10,000 grams of glaze (about 2⁄3 of a standard 5-gallon bucket) would be around $264. In comparison, the addition of 0.005% chromium oxide and 5% tin oxide to 10,000 grams of glaze would cost around $141 (the large majority of this due to the addition of tin oxide, as the chromium oxide alone would only cost three cents).

Other pink glazes tend to be difficult to use and are limited to specific conditions, such as coating thickness and firing temperatures.

In attempts to create a new pink standard, one that is highly more affordable and easier to use, we started with the raspberry chromium oxide glaze. This glaze has a high cassiterite concentration (tin oxide (SnO2)). Cassiterite forms a crystal structure which helps prevent light from traveling through the glaze—creating an opacifying effect. In order to produce pink (rather than a deep red), we started scaling back the amount of chromium oxide introduced to the 5% SnO2 glaze from figure 2, as that was when a clear, unmuddied red was first observed. If there is a lower concentration of chromium oxide to occupy the tin crystal lattice, and the same overall opacity, a lower saturation and more pastel red should be found. After eighteen chromium down-ramps, we found that while most red chromium glazes use around 0.2% chromium oxide, even 0.005% chromium oxide was enough to produce a soft pink, while anything at or above 0.025% seems to transition back toward the deeper raspberry red colors (4).

While these chromium amounts yield the desired shades of pink, they also produce speckles—possibly due to concentrated color centers. These color centers likely arise from defects in the structure of the tin-chromium lattice. While the speckling may be an effect that is desirable to some, it can be reduced by using a ball mill to evenly distribute the chromium oxide.5

With pinks set, it was pondered if purples could also be developed the same way. Traditionally, purples (similarly to pinks) are hard. The most common purple is neodymium oxide, making a dichroic lavender. It has about the same cost as erbium: $120/pound. And the pigment loading for neodymium is about the same, ringing in at 8% or so. That’s more than $200 for a bucket in just pigment alone.

Cobalt is a relatively strong pigment (but not so sensitive as chromium in tin, as shown earlier), so it was added in 0.05% increments and then doubled in the last row at 0.40%. This made for quite a colorful set of glazes that, to our knowledge, hasn’t been developed or shared to this date (5).

Raspberry Base Recipe

This is the base recipe for tin and chrome glazes to produce pinks and purples. Ferro frit 3134 provides a high calcium content that is essential in achieving the desired pink color.6 Calcium (in Ferro frit 3134) helps achieve opacity in the glaze at higher temperatures.7 It should also be noted that zinc should be avoided in this glaze recipe as it results in varying shades of brown. This could be because zinc could compete with chromium for open sites in the cassiterite crystal matrix (which chromium otherwise occupies and results in vibrant pinks and raspberries).

varying shades of brown. This could be because zinc could compete with chromium for open sites in the cassiterite crystal matrix (which chromium otherwise occupies and results in vibrant pinks and raspberries).

To obtain Julia’s Pink, as seen in the first mug for this article, add 0.010% Cr2O3 to the Raspberry Base Recipe. Be sure to pay attention to decimal places. It will be a very small amount of chromium!

While the exact mechanism for chromium-tin pink and raspberry glazes is not currently fully agreed upon, several different phenomena are taking place, including nanoparticle formation, chromium substitution in cassiterite matrix, and likely competition between Cr and Sn for that matrix position. It is interesting that nanomaterial quantities of chromium oxide are required for vibrant pinks and reds—much akin to metal loading content for nanoparticle gold and silver glazes as well.

Hopefully, this grid of pinks to purples helps those in need and inspires others to look at commonly used recipes and ask themselves how they work—and then start changing additives in the recipes. This range of pinks and purples has been sitting under potters’ noses for a decade now, just waiting for someone to ask how it works.

the authors Julia Krichev is a swimmer at the University of Richmond. She is currently studying biochemistry and visual arts at the University of Richmond.

Craig Caudill is currently pursuing a master’s of public health in epidemiology at the University of Michigan. He is a recent graduate from the University of Richmond, earning a BA with honors in leadership studies.

Ryan Coppage is currently chemistry teaching faculty at the University of Richmond. He fiddles with various glaze projects and makes a reasonable number of pots. To see more, visit www.ryancoppage.com.

1 Castro, R. H. R. et al. Surface Segregation in Chromium-Doped Nanocrystalline Tin Dioxide Pigments. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 95, 170–176 (2012).

2 Amendola, V., Pilot, R., Frasconi, M., Maragò, O. M. & Iatì, M. A. Surface plasmon resonance in gold nanoparticles: a review. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 203002 (2017).

3 Julián, B. et al. A Study of the Method of Synthesis and Chromatic Properties of the Cr-SnO2 Pigment. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 2694–2700 (2002).

4 Tena, M. A. et al. Study of Cr-SnO2 ceramic pigment and of Ti/Sn ratio on formation and coloration of these materials. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 27, 215–221 (2007).

5 Technofile: Demystifying Chrome Oxide for Fantastic Ceramic Glaze Color. https://ceramicartsnetwork.org/daily/article/Technofile-Demystifying-Chrome-Oxide-for-Fantastic-Ceramic-Glaze-Color.

6 Ibid.

7 Opacifiers. https://ceramicartsnetwork.org/ceramic-recipes/recipe/Opacifiers.

October 2025: Table of Contents

Must-Reads from Ceramics Monthly

Unfamiliar with any terms in this article? Browse our glossary of pottery terms!

Click the cover image to return to the Table of Contents